On a storm-lashed January morning, engineer-turned-activist Lea Kovic stood on an exposed Atlantic pier, gazing into the water as though waiting for a reply. Fishing boats rocked in heavy swells, their engines swallowed by the roar of the sea. Far below those steel-grey waves, beneath foam and circling gulls, governments and technology giants are proposing to send a high-speed bullet train through the ocean’s depths.

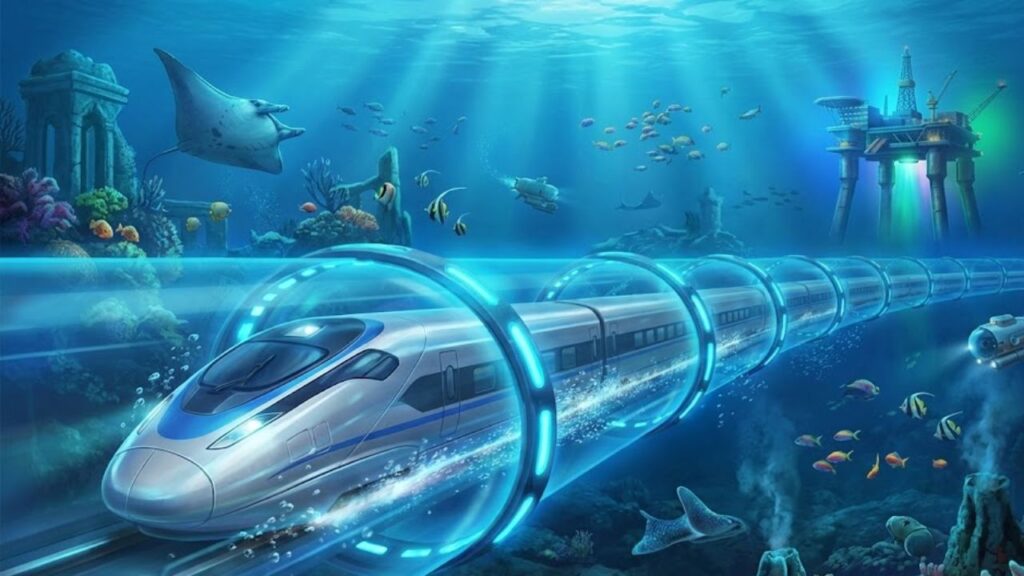

She pictures it clearly: a glass-and-steel corridor slicing through the seabed, capsules racing past whales at 600 km/h. Tickets promising New York to London in under two hours. A so-called new Silk Road built for an impatient, hyper-connected world.

Then she speaks softly: “Once you cut a highway into the ocean, you can’t undo it.”

Supporters hail the proposal as the future of transport.

Goodbye to Old Licence Rules: Older Drivers Face New Renewal Requirements From February 2026

Goodbye to Old Licence Rules: Older Drivers Face New Renewal Requirements From February 2026

Opponents describe it as an environmental crime.

Why an Underwater Train Is Drawing Global Attention

The concept sounds lifted from science fiction. A sealed, high-speed train would travel inside pressurised tubes laid across the ocean floor, linking continents. Promotional visuals show sleek capsules gliding through glowing blue water, passengers sipping coffee as sharks drift past outside.

The pitch is polished: jet-lag-free journeys, lower carbon travel, and a new chapter of global connection. For politicians eager to cut aviation emissions without slowing economies, the idea is tempting. For investors, it looks like the next major moonshot.

Below the surface, however, marine scientists, island nations, and Indigenous coastal communities are studying the same plans with deep concern.

One leaked feasibility report for an Atlantic route shows a tunnel line passing directly through known migration paths of humpback and fin whales. On paper, it’s a clean line. In reality, it cuts across a living corridor already filled with movement and sound.

Near Iceland, researchers are modelling the effects of continuous low-frequency vibrations such trains could generate. Early simulations point to a permanent noise halo extending hundreds of kilometres, a mechanical presence that never fully fades.

- How banana peels help plants only when placed in the right spot

- Pension increases from February 8 tied to a missing certificate requirement

- Why wearing jeans in extreme cold is strongly discouraged

- Hundreds of US flights cancelled and thousands delayed across major hubs

- How Switzerland built vast underground infrastructure over decades

- The longest total solar eclipse until 2114, visible from Italy

- France losing a multi-billion-euro Rafale deal after a sudden reversal

- China creating new islands by dumping sand into the sea

Fishermen near proposed landfall zones worry most about the construction phase: dredging, blasting, concrete bases, and endless loads of steel and rock. One summed it up quietly: “If this happens, my son may be the last in our family to fish here.”

On land, humanity is used to cutting through landscapes. The scars are visible, familiar, and often ignored. Underwater, the damage is hidden.

That invisibility is exactly what alarms critics. A tunnel bored deep into the seabed is not just a silent tube. It brings seismic shocks during construction, sediment plumes carried by currents, and a permanent chain of maintenance hubs, cables, and power systems. Each adds noise, heat, and chemical runoff to ecosystems shaped by long-term stability.

A high-speed underwater train wouldn’t simply link continents; it would anchor heavy industry in places we barely understand.

The Real Price Behind the Promise of Progress

If the project moves forward, the first visible sign won’t be a train. It will be fleets of ships. Survey vessels dragging sonar across the seabed, drilling rigs punching into deep sediment, barges deploying sensors and explosives for seismic testing.

Campaigners in Portugal and Canada are already tracking these early activities using binoculars and open-source shipping data. They call this stage “the creeping phase”—when nothing is officially approved, yet the ocean is quietly converted into data, maps, and profit forecasts.

Activists share a simple warning: pay attention to the small contracts. Environmental reviews, temporary test platforms, auxiliary ports. That’s where irreversible change often begins.

Many still view the ocean as limitless and self-healing. We dump, drill, and blast, assuming tides will erase the damage. Then we act shocked when coral bleaches, fish stocks collapse, and coastal storms grow stronger.

Supporters frame the underwater train as a clean alternative to aviation. Fewer long-haul flights look good on climate charts. Critics argue that comparison misses the point. A permanent tunnel system would stack on top of existing pressures like deep-sea mining, container shipping, offshore drilling, and plastic pollution.

Few people read hundreds of pages of environmental assessments cover to cover. That’s often how dangerous shortcuts pass unnoticed.

The most vocal opponents are blunt. They describe the project not as innovation, but as a last attempt to stretch an exhausted growth model beyond planetary limits.

“This isn’t transport. It’s the colonisation of the deep,” says marine ecologist Dr. Rahul Menon. “We’re exporting a broken relationship with land into oceans already under severe stress.”

Leaked investor slides include a chilling phrase: “Unlocking undersea real estate value.” Three words that reduce living oceans to a spreadsheet of assets.

- Noise: constant low-frequency rumble disrupting whales and fish

- Light: artificial glow from hubs leaking into dark zones

- Chemicals: lubricants, coatings, and microplastics entering currents

- Heat: warming plumes around power systems altering ecosystems

- Ports and access roads: new coastal scars encouraging further industrialisation

Who Benefits From a Faster World?

Viewed broadly, the underwater train is less about technology and more about our addiction to speed. A ninety-minute Atlantic crossing sounds thrilling, but it assumes a world that is always on, always reachable, always accelerating.

For global-city professionals, the idea of breakfast in Paris and lunch in New York feels irresistible. For a coastal resident watching another “strategic hub” rise on their shoreline, it feels like someone else’s ambition reshaping their home.

A quiet question lingers beneath the hype: who is this really for?

Shiny tech promises often make life look smoother and easier—at first glance. Then reality intervenes. Someone always bears the cost, often communities that never asked for the change.

Critics say the underwater train follows this familiar pattern. The most affected groups—Indigenous Arctic fishers, small island nations, and coastal towns from Ireland to Morocco—are still fighting for meaningful inclusion. Their questions are direct: What happens to our fisheries? Who is responsible if something fails four thousand metres down? Who defines acceptable damage?

Engineers respond with charts and softened worst-case scenarios. Politicians speak of balance. Yet one phrase continues to surface from opponents, charged and difficult to dismiss: environmental crime.

Is the “Environmental Crime” Label Justified?

Critics use the term to emphasise intent and scale. This would not be a minor error, but a deliberate move to industrialise fragile, poorly understood ecosystems despite long-standing warnings about ocean health.

Could the project ever be sustainable?

Supporters claim that strict safeguards, cleaner construction, and marine zoning could reduce harm. Opponents argue that some areas—deep trenches and major migration routes—should remain off-limits.

What about jobs and economic benefits?

Backers promise tens of thousands of high-skilled jobs and revitalised ports. Coastal communities respond that construction booms are temporary, while traditional livelihoods often vanish quietly.

Would it meaningfully cut aviation emissions?

Possibly, but only if it replaces existing flights rather than creating new demand. Some climate researchers warn that mega-projects often add travel instead of substituting it.

Can the momentum be slowed?

Activists point to tools like international ocean treaties, legal action for future generations, citizen monitoring of surveys, and sustained media scrutiny.

- Deep oceans aren’t empty: They are dense with life, migration paths, and fragile ecosystems.

- “Green” labels can mislead: Cleaner than planes doesn’t mean harmless when added to existing pressures.

- Public scrutiny still matters: Surveys, impact reviews, and local hearings remain leverage points.